|

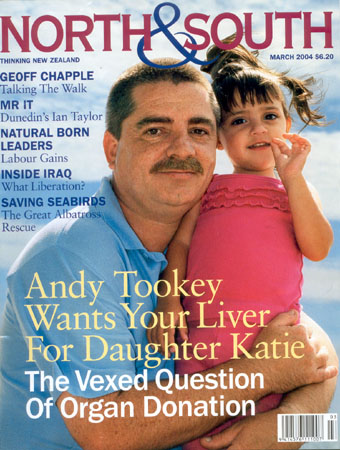

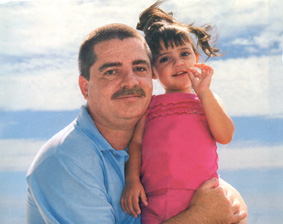

One day soon two-year-old Katie Tookey will need a liver transplant. Her father Andy's campaign to improve organ donor rates and ensure she gets one has made him unpopular in some medical circles. JENNY CHAMBERLAIN discovers parting with your spare parts is not as straightforward as you think. To Give Or Not To Give?

You think, because you ticked the donor box on your driver's licence, that when you die several very sick people will get your healthy organs - and get their lives back. You are almost certainly wrong. Andy Tookey is convinced a national awareness campaign is the best way to raise New Zealand's low rate of organ donation but medical professionals believe he's wrong too. The 380 New Zealanders currently awaiting organ transplants would say Andy Tookey's heart's in the right place. And, if he has his way, yours could be too -- plus your other pre-loved bits. The North Shore organ donor campaigner would very much like us all to feel "morally obliged" to say yes to organ donation. This change of heart he says will turn around our low donor rate and save lives and money. For, despite a national reputation for generosity, only 40 New Zealanders became organ donors in 2003 - a rate of 10 donors per million, placing us 16th in a list of 19 developed countries and leaving many despairing of ever getting the organs they need. Top of the chops is Spain which uses a system of "moral" persuasion very different from our gently, gently approach - resulting in a 32.5 per million donor rate. To fix New Zealand's organ shortage, the determined Cardiff born, former cruise ship entertainment officer has transformed himself into the Tookinator, and set up Give Life NZ, a one-man non-profit organisation, campaigning for organ donor reform. An ability to amuse is useful for parlaying what could seem a predatory role into a persuasive performance and Andy Tookey's grin belies his grit. After a couple of hours listening to his smooth delivery it's no surprise to learn that "once this is over" he plans a career in politics. "A friend told me you only need a big ego and half a brain to be an MP and I thought that's me!" He'll set up his own party and "go for the top. Why mess with the monkeys when I can go with the organ grinders?" he quips. Organ grinder headquarters is a converted carport with a pink-painted interior beside the Mairangi Bay, North Shore house where Tookey, wife Janice and children Bradley (10), Katie (two) and Gregory (11 months) live. The shelves are tight-packed with papers, there's a battered sofa and a noticeboard. At centre, on a small desk, is Tookey's computer -the hub of a worldwide web of donor and transplant information. Ask him anything and Tookey will grab the mouse, or leap up to riffle through clips, reports and files while continuing his flow of info. His detractors, medical professionals who deal daily with organ donation -under whose skin Tookey has firmly got - say he's less than accurate. But when it comes to stats and facts Tookey's never stumped. The press come to him for comment now, he says.

Recipients, donors, people on the waiting list, overseas organ donation campaigners - hundreds keep in touch. "I'm seen as the national spokesperson. You can't get hold of the national donor co-ordinators when you want them and they're not in the phone book. In other countries there's a shop in the high street where the public can pop in for information," he says. Never underestimate the power of the lone campaigner. Janice works shifts at Sky City and Tookey fits his mission round his share of childcare and his job as a video technician at a local school. Two years' persistence has generated considerable coverage for the spare parts business, which began in New Zealand in the 1940s with corneal grafting and which has advanced dramatically over the last 20 years: heart transplantation began here in 1987, skin transplantation in 1991, lungs in 1993, liver and pancreas in 1998. In 2003, the organs from our 40 donors resulted in approximately 200 transplant procedures (68 kidneys, 25 hearts, 23 lungs, 33 livers and up to 50 cornea, heart valve or bone transplants) and as many happy recipients. The cost was $11 million -up from $6 million five years ago. All transplant stories are grist for Tookey's media mill which includes local and national newspaper items, women's mag pieces, backing from filmmaker Peter Jackson, spots on Holmes, a promotional video entitled Everyday Heroes directed by late teenage filmmaker and, cancer victim Cameron Duncan - which won the 2003 Fair Go Ad Awards and will screen soon on Prime - talkback, a petition signed by 1169 locals, and a charity auction at the LOTR pre-launch dinner in December 2003 which raised $13,107. Tookey's website www.GiveLife.org.nz averages 13,310 hits a month. "I work constantly on my new-found friends in the press to keep the issue alive," says Tookey, who is both catching the current mood and helping create it. Media coverage almost exclusively focuses on organ donation as a solace for grief. Following the tragic drownings of their seven-year-old son Joshua and 16-year-old daughter Christie at Browns Bay beach in January this year, American couple Mark and Vivienne Robinson's announcement that Christie's organs would be donated as a "gift of thanks" for support and to "help save lives in other families" made front page news. Tookey says a woman rang Newstalk ZB last year to say that, as a direct result of seeing him on television, she had donated the organs of her 18 - year-old daughter who'd died in a car crash a few days after he'd appeared. "It's possible what I have been doing has already saved lives," he says. Tookey's moment of triumph came in December 2003 with the release of the Health Select Committee set of recommendations on organ donation. Tookey made his submission on September 17 2003 and is delighted the committee's list so closely matches his own and includes public awareness, education for health professionals, setting up a register and national protocols for gaining consent. "I can't believe not one doctor, or the transplant service, have contacted me to say thanks, or well done or leave us alone! Just shows you how much they hold me in contempt," he says. Those who control organ donation in New Zealand don't want a bar of Give Life NZ, Tookey or his campaign. At the risk of being classed a "vulture" Tookey will ask questions others shrink from. When rally driver Possum Bourne died in April 2003 Tookey tried to find out if he was a donor. "I never heard back but if he was he would have been a hero in death, as he was in life." He asked Jonah Lomu's manager Phil Kingsley- Jones if Lomu - who needs a kidney transplant t- would become involved but no joy there either. Lomu could have been our Michael Jordan - who went public as being pro-donation and raised donor rates among African-Americans. | One Million New Zealanders have ticked the organ donor box on their licence believing that settles the matter but, as Andy Tookey quickly found, it means virtually nothing. | Awareness will lift us out of the donor doldrums, says Tookey. He cites the "Nicholas Effect" -the story of seven- year-old American Nicholas Green who was shot in a botched robbery while travelling by car with his family in Calabria, Italy, in 1994. Nicholas' parents, Reg and Maggie Green, donated his organs and seven Italian recipients benefited. The Greens' action doubled the Italian organ donor rate - placing that country eighth on the organ donor chart. Why "absolutely nothing" is being done to educate the public is beyond Tookey - though of course he's now doing it for free and rather well. He says he's offered his video several times to Health minister Annette King and Colin Feek, Deputy Director-General of Clinical Services in the Ministry of Health and they have refused. "Instead of them paying $200,000 of taxpayer money to make an ad and then pay for the airtime here is one for free. All I was asking for was help in getting the airtime. It doesn't really inspire me that they are going to be very enthusiastic about a campaign in the future."

He claims Auckland - based National Transplant Donor Co-ordinator Janice Langiands won't return his calls or emails. "Me and Janice don't see eye to eye," he says. The story of why Andy Tookey started this campaign provides the bones of how organ donation works or, as he would claim, doesn't work here. Little Katie Tookey, a mischievous, big-eyed mini version of her dad, was born with biliary atresia a destructive liver disease in which the ducts which drain the bile from the liver progressively block, resulting in cirrhosis (death of liver cells). It affects one in 15,000 babies and is incurable. Katie has 20 per cent cirrhosis and will need a liver transplant probably within 10 years. Meantime you'd never know the adventurous mite, who loves dancing and Noddy, has the disease. Her tummy's a bit swollen; she's smaller than other two-year-olds but she has started going to playgroup to catch up on some of the socialisation she has missed through frequent infections. Tookey says Katie only needs a quarter of an adult liver - but she's not yet ill enough to go on the waiting list. The Tookeys are "constantly watching" for signs she is becoming unwell. "In a normal child a temperature could be a cold coming on but with her we don't know." While it's possible for Tookey to give Katie part of his own liver, surgeons won't risk it. If he died in surgery, who would provide and care for Katie? Tauranga grandmother Suzanne Callander became the country's second live liver donor when, in January 2003, she gave a quarter of her liver to 16-month-old grandson Brady Anderson. Brady also had biliary atresia but his condition was more serious than Katie's. Currently 15 New Zealanders are waiting for liver transplants. Tookey fears that by the time Katie's turn comes that number will have increased "exponentially" and her name will go further down the list. On receipt of the devastating news of her diagnosis, Tookey immediately went to register as a donor on his driver's licence. He'd ticked no first time round because, he explains, "there was no information and because I'd read somewhere that if they know you're a donor they'll let you die because they need the parts".

He discovered he needed to reapply for a new licence and pay $32 just to change his no to yes. "How many other people wanting to be altruistic would be prepared to go through the hoops to do that? That's when I decided to investigate the system and found all the red tape that discourages people from becoming donors."

It's absolutely true that only a few intending donors get to give life after death. Here's why: One million New Zealanders have ticked the organ donor box on their licence believing that settles the matter but, as Tookey quickly found, it means virtually nothing. Organs can only be transplanted from brain-dead people whose vital functions are being artificially maintained in an intensive care unit. Only around 1400 people a year die in our 23 ICUs. That figure would cover the waiting list three times but of course not all ICU deaths result in useable organs. And ICU personnel in New Zealand don't check driver licences or the LTSA database to see if a brain dead patient ticked the box - they ask the family. And often, if the family is too distressed, they don't ask at all. To Tookey this means the brain-dead person who ticked yes is not having his or her wishes "respected". It may come as a surprise to you but under the terms of the 1964 Human Tissue Act you don't own your body after you die. If you die in hospital, the chief medical officer is the person "lawfully in possession" of your corpse. In theory, if you ticked yes, you're declared brain dead, your organs are suitable and the intensivists looking after you haven't switched off the machinery too soon, the hospital head can authorise the collection and use of your body parts. In practice this never happens. As liver transplant surgeon Stephen Munn puts it: "If we ever removed the organs against the family's wish that would be the last set of organs we would ever get."

Families are always asked for consent and a 1999 study shows around half refuse. Overseas instances where authorities have removed organs without consulting the family have backlashed in the form of plummeting donor rates. In New Zealand the news that Green Lane Hospital held a library of 1354 children's hearts, collected mostly without the consent or knowledge of the parents, caused a media storm and considerable anguish. The family right of veto is hugely frustrating to Tookey, pro-donors, transplant surgeons, those waiting desperately for organs, and people like Dr Martin Wilkinson, a senior lecturer in community health at the University of Auckland, who told a medical conference in Wellington last year that consent for organ donation was overrated. "I am advocating the information should be out there so people can make an informed choice and, if they choose to be a donor, the current barriers [to donation] are removed," says Tookey. He suggests a change in semantics: "South Australia has a 22 per million donor rate. In New Zealand they say, 'Your husband's died, can we have his organs?' Of course the immediate reaction is, 'No, no, no'. In South Australia they say, 'Your husband's died and his wishes" were to be an organ donor and we would like to respect his wishes, unless you have a strong objection.' They just word it differently. I'm trying to change ours to the South Australian system."

In fact South Australia had 20.7 donors per million in 2002, which dropped to 14.4 in 2003 - a startling decline no-one, here or there, can explain. At nine donors per million Australia's overall donor rate is lower than New Zealand's -despite the fact Australia spends $3 million a year on public education. Interestingly South Australia is home to Adelaide-based anti- transplant campaigner Norm Barber - whose activities we'll come to soon. Meanwhile add payment for live donors and scout nurses, whose job it would be to search hospital wards for potential donors -"we lose a lot because they die [outside the ICUs]" - and you've got Tookey's pragmatic wish list for sorting a situation he says is "such a mess, even if Katie gets a liver tomorrow I would see this through to the end".

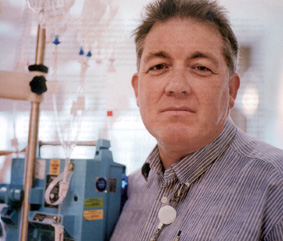

Maybe raising the Tookinator's campaign with Auckland Hospital intensivist Stephen Streat at lO.30am on a Saturday, when Streat hasn't had more than four hours' sleep for several nights in a row, isn't the best move. Streat, a kindly, comfortable man - one of six intensivists who run the airy 24-bed unit on the eighth floor of the hospital's smart new building - clamps the end of my preamble with a snapped question, born of irritation and bone weariness: "Are you writing a story about organ donation or transplantation? Organ donation is not a subspecialty of transplantation; it is part of end of life care in intensive care." This simple yet subtle distinction defines the gulf between Andy Tookey and the man widely regarded as the country's leading authority on the relationship between brain death, organ donation and the work of intensive care specialists -the people who control organ donation in New Zealand. In most minds donation and transplantation blur together, maybe because we are dimly aware only a few hours' surgical wizardry separate the death of the donor from the new life of the recipient. It's a topic to which Streat brings 28 years' medical experience, the last 20 of those as an intensivist in daily contact with donor families. He has published extensively, has thought and fought his way through the tangle of ethical issues surrounding organ donation, has talked with hundreds of families and guided them through the donation decision-making process and he knows where he stands. | "The human body is more than just another chattel to be disposed of, like a boat or a Mercedes."

-Auckland Hospital Intensive care specialist Stephen Streat |

Streat is implacably opposed to most of what Tookey suggests and, with national transplant donor co-ordinators Janice Langiands and Dawn Kelly, bitterly opposes the growing body of opinion which holds it is our moral duty to be treated in a utilitarian way after we die. "We have both, Langiands more than me, put up with an endless litany of journalists, reporters, TV presenters and well-intentioned zealots wishing to promote stories about the 'organ donor shortage, who is to blame and how it should be fixed'," says Streat. "With the exception of me, Janice and Dawn, everyone speaks about organ donation not from the perspective of good process [for the donor] and the truths learnt at that encounter but about the need for more organs for transplant. I think that whole agenda needs to be exposed." In other words the debate goes deeper than ticking boxes and he seems surprised and pleased North & South is willing to listen. When Streat started out as a trainee physician working in nephrology in 1976 - in the days when only corneas, kidneys and heart valves were being transplanted here - discussions with families were done by transplant surgeons. "The transplanter came along as a representative of the recipients and the discussion was a request for organs - asking for their generosity. "Intensivists, says Streat, were very uncomfortable with that and with the dual role of being the life and death team and also something to do with transplants. "We were afraid families would perceive a conflict of interest and would infer we were treating people as sources of organs and limiting access to good intensive care because we thought they might be donors. We wished to avoid that." During the 1980s intensivists took on the role of "facilitating the decision-making process" -that is talking about donation with families who sit sadly with brain-dead loved ones in ICUs. It's a hugely skilled role, says Streat, and the intensivist, who manages treatment and interacts with patient, family, medical and nursing staff, is the best person to do it. "Organ donation is just a tiny little bit on the end of all that," says Streat. The Australian New Zealand Intensive Care Society has formulated a code of practice and set of guidelines for the determination of brain death and organ donation which is currently in its third revision. Streat runs one-day training programmes for intensive care doctors on the topic - thus far only 35 New Zealand intensivists have attended them. He wishes more would sign up. Streat, a lapsed Catholic who supports organ donation and transplantation, believes the intensivist's role is to adopt a "morally neutral" position. He upholds the family right to veto and says his job is to guide them through their decision and support them in it, whether it's yes or no. "I believe an individual's spirituality and dignity are not things the state or others have a right to subsume or demand. And this applies to your body after you're dead. People have strong attachments to people they love. This doesn't stop the moment they die. If we, in a utilitarian way, ride over that, then we are debasing something about our humanity and spirituality." The human body is more, says Streat, than just another chattel to be disposed of, like a boat or a Mercedes.

Comforting words to those who find utterly repugnant the idea of being "morally obliged" to allow the still-pink, still-breathing, still-urinating bodies of the people they love to be wheeled away for organ retrieval. "I can tell you my belief is pretty damn unique in transplant medicine," says Streat. Organ donation has been captured by what is variously called rational utilitarianism or the communitarian movement, he says. "People are dying on waiting lists, their need is great and people believe doing the right thing by them is their moral and civic duty. That by virtue of availing yourself of the health benefits of living in the 21st century you have a communitarian duty after death to contribute all your transplantable organs."

Surgical skill and immunosuppressant drugs which block organ rejection have turned the cadaver from something to be disposed into a vital resource. To discover how far thinking has gone on rights of access to this resource, Google search "organ donation" and among the millions of entries you'll find papers by utilitarians like Harry Emson, a Manchester-born 75-year-old forensic pathologist (still practising part-time in Saskatchewan, Canada). Emson sums up the ultimate expression of the approach in It Is Immoral To Require Consent For Cadaver Organ Donation, published in the journal Of Medical Ethics, 2003: "Any concept of property in the human body either during life or after death is biologically inaccurate and morally wrong... the human body can only legitimately be regarded as on extended loan from the biomass... it is morally unacceptable for the relatives of the deceased to deny utilisation of the cadaver as a source of transplantable organs". Emson suggests the best way of eliminating the family's agony over deciding is to "make the human cadaver the charge and responsibility of the state to determine its best disposition". This is what Streat stands against. And to him there should be a brick wall between donation and transplantation. As someone whose life is devoted to doing everything in his power to bringing people back from the brink of death it’s the only way he can remain an "honest broker". Everything about Tookey's approach - the fact his motivation is based on personal need and his fundamental aim is to "get more organs" - is anathema to the intensivist. When TV2's Flipside contacted Streat in October 2003 to appear with Tookey, Streat refused. The producer dropped Tookey and Streat got a couple of minutes on his own.

Streat is in the unique position of seeing brain-dead patients wheeled out of his equipment - festooned, softly-beeping ICU to the operating theatres to have their organs retrieved and then, some hours later, the recipients of those organs wheeled in. Like anyone, he rejoices in the "magical transaction. The recipient gets an entirely new lease of life," he says. Sometimes it's just slowing a rate of decline but it can mean they "go out and buy a leather jacket and a Harley, or return to tennis". He believes the culture of compulsion which is creeping into the organ donor debate will cause a decline in these magical transactions. "New Zealanders and Australians are generous people. We are not very rich but we contribute strongly to charities. Not because somebody tells us to but because we want to, out of a sense of community and egalitarianism. But when people tell us we should do things our national response is very stubborn and obstinate. We tend to say, 'Hell no!'

"Utilitarians would have you believe, and Andy Tookey would support this, that it should become my responsibility to represent to the family that this is what the donor wanted and that that wish has greater moral legitimacy than [the family's] wishes. The words used are: 'Let's respect the donor's wishes.' Am I going to do that? I am not going to do that! The donor's wishes are part of the currency of the discussion along with a whole lot of other things and I will ensure they are all discussed: what the donor wanted, what the benefits to subsequent transplant recipients would be, what exactly goes on in the operating room, how the body will be treated, when they will be able to see the body again, will it affect the ability to have an open casket. And I will ask, 'How do you feel about it? What do you want?'" Aren't families in too much shock to cope with all this information? "I've done this discussion many times, so have my colleagues and, guess what? Families can and do cope. They don't necessarily process it in a way that's rational but they do deal with it with dignity and respect." There is another donation myth which he's keen to bust: "That organ donation makes your grieving better; gives you something good out of something bad. A study done in Holland looked at the quality of bereavement outcomes and showed there is no difference between families who never have this discussed families who discuss donation and decline and families who discuss and agree. People simply look back and make an interpretation that their grieving was better because of organ donation." Streat strongly rejects some of the Health Select Committee recommendations. National awareness campaigns and organ donor registers are both costly measures which have proved ineffectual overseas. "Registers are expensive, are taken up by a minority of people, , create moral and ethical problems of their own and do not increase donor numbers."

He doesn't support developing protocols for "gaining consent from next of kin" but wants them for discussions with families. What he wants is more funding for ongoing education for ICU health professionals to ensure they're more aware of the importance of preserving organs for possible transplant. "There are potential donor families who never get to have the discussion," says Streat - because the medical care of the patient's organs during the dying process is not appropriate for possible donation.

"I don’t believe in

guilting people

into this. We very

gently persuade by

feel-good stories. The

longest-lasting kidney

transplant is more

than 30 years. The

goodness donors

do can go on for a

long time." Auckland Hospital national liver Transplant unit head Stephen Munn

He would like public awareness to focus not on increasing donor rates but on "the enormous benefits to recipients of transplantation" - a subtle but important difference which would increase donor rates slowly over time.

He agrees with the proposal to establish a national organ donation agency -essentially an expanded, better - funded version of the agency managed by Janice Langlands which is funded through the Auckland District Health Board with a lean budget of $254,000. Langlands has no secretarial help and no resources to even distribute pamphlets. Ideally Streat, Langlands and Kelly would run the new organisation.

The encouragement of general family-based discussion of organ donation would belong under the aegis of this national agency and not be left to "well-intentioned but ill-informed proselytisers", says Streat.

Streat's sensitive approach "may not produce more organ donors but it might more accurately reflect society's true level of support for organ donation", which, he says, is not great. "There are a variety of reasons for this, some to do with queasiness about organ donation but also some people wonder why. Why we can cheerfully spend a couple of hundred thousand transplanting somebody when people linger for five years in pain on waiting lists for joint replacements?

"Transplantation is a good thing for recipients and I strongly support it but it's only part of an overall health care system which in this country is bloody struggling to cope. If we double the number of organ donors here there is not money from government for that volume of transplant work.

"It is undoubtedly true that people who receive a good functioning transplant go back to work and contribute to neighbourhood and society and family. However they cost [for the immunosuppressants]. And does everyone generate a net economic input greater than their economic cost? That's the kind of question that politicians ask."

Are transplant surgeons with Tookey or Streat? The short answer is somewhere between the two.

Masterton - born Stephen Munn trained in transplant surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and returned to New Zealand to set up Auckland Hospital's national liver transplant unit in 1998. (The unit also transplants kidneys.) Munn is one of only two New Zealand surgeons focussing solely on transplants he's done 250 thus far. The other is Motohiko Yasutomi, the Japanese surgeon Munn trained at the Mayo Clinic, whom he hired to work with him here.

Munn's is the smiling face of the organ business - "I enjoy my job enormously". But he's not happy with the rate of organ donation in New Zealand. A 20 per cent increase, he says, would mean fewer people would die on the waiting list.

Andy Tookey worries about Katie's prospects, but Munn confirms New Zealanders waiting for livers have a fairly good chance of receiving a transplant. About 12 currently wait and Munn's unit is contracted to transplant 45 livers a year - 39 adults and six children. Livers, are expensive - assessment, travel, accommodation, surgery and 90 days of post -transplant care costs $140,000 for an adult liver recipient and $180,000 for a child. The cost of immunosuppressants is $10,000 a year for life. "We get about 40 livers from New Zealand a year and we import around 10 from Australia."

(If these numbers don't add up neatly it's because people move on and off the waiting list and it's possible for one liver to be divided between more than one recipient.)

The most common reason for needing a liver is Hepatitis B, a preventable disease which can be eradicated by early vaccination. The unit takes a pro-active role in Hep B screening and vaccination promotion. Streat says the largest untreated cohort are Hepatitis C patients who contracted their disease from intravenous drug use in the 60s and 70s and are only now getting cirrhosis and needing transplants.

Most disadvantaged are patients with acute liver failure - caused by adult Hep B infection or, more rarely, attempted suicide by Paracetamol overdose. For this small group prognosis is poor - with only about three days from wait listing to death. About 40 per cent don't receive a liver in time.

Munn does not predict an exponential increase in the future need for livers but kidneys are a different matter. The overwhelming majority of people - around 350 - on the transplant waiting list are waiting for kidneys and this number is going up and will continue to increase, he says.

He estimates a donor rate increase of 20 per cent would save about $5 million over five years. Dialysis numbers are growing seven per cent a year: "Auckland's dialysis unit has two shifts a day and is on the threshold of needing three. If we can hold that back to two we'd save money. It costs about $50,000 a year to keep a person on dialysis. The transplant is a one-off cost of $70,000 but thereafter only $10,000 a year [for the immunosuppressants]."

Munn aligns himself more with Stephen Streat than Andy Tookey. He says transplant surgeons "carefully dissociate ourselves from declaration of brain death and from anything to do with a patient until we get offered the organs. Only then do we participate in the fluid management of the patient."

He says a national awareness campaign would be great if there was unlimited money but it would need to be repeated every few years because the knowledge would dissipate. "Our priority would be to put the money into education in the ICUs because that's where the donors are."

While he doesn't like the term scout nurse he does feel it would help if someone in each unit did "a real time death audit - look at every death that occurred and ask could this person have been a donor? Are we doing as well as we could possibly do?

"I don't believe in guilting people into this. The only way is to make sure people feel as comfortable as possible about the decision. We very gently persuade by feel - good stories. The longest - lasting kidney transplant is more than 30 years. The goodness donors do can go on for a long time."

Since New Zealand's first heart transplant in 1987 more than 145 hearts have been transplanted at Green Lane Hospital but our longest-surviving heart recipient is North Shore resident Ron Gray, 68, who received the heart of a 19 -year-old male motorcycle accident victim at St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney, in January 1985.

Gray's own heart was damaged by the impact of a ball during a game of cricket. Apart from his recuperation, Gray "never stopped working" - he retired from a job in real estate five years ago. He walks regularly, helps with meals on wheels, belongs to Lions and coaches and referees soccer. His immunosuppressant drug Cyclosporin costs $6000 a year. Gray has two sons, two daughters and six grandchildren. He walks with a slight limp due to a mild stroke he suffered just before the transplant. His 19-year-old gifted heart doubled its age this January and it's ticking along "just fine".

So, what about the less rosy side of things? Email standardoil@hotmail.com and you can request a copy of Adelaide activist Norm Barber's book The Nasty Side of Organ Transplanting. Norm isn't big on providing bio but his previous publications {How To .Become A Successful Derelict in Adelaide and How to Have a Successful Nervous Breakdown in Adelaide} suggest he's not as average as his name suggests. In a short email he says he is a 54-year-old Canadian who moved to Australia in 1972. "I am quite unpopular with the major media...

a nobody, uneducated, a bit lazy, who likes to investigate certain subjects for the thrill of discovering how experts and those in power lie to everyday people."

The book's 120 pages aren't a cosy read. Basically they contain a vehement denunciation of the "transplant industry" and all the nightmare things Barber believes happen: "Consent based on ignorance! Harvesting begun while the donor is partly alive, organs and body materials used for ineffective treatments or cosmetic surgery". It took Barber two years to research the book and it's into its third edition. One wonders if its popularity is connected with South Australia's drop in donor rates. At the very least, grisly descriptions and emotive language aside, it contains enough verifiable information to force us to question where organ donation is heading.

Barber points out that in the US the commercial sale of donated organs and tissues is common practice - something unthinkable in New Zealand. He alleges that foundations set up to encourage the altruistic donation of organs run body parts businesses on the side and make big money.

One resource is the bodies of the poor. "In 1998 Clinton administration legislation forced United States hospitals that receive Medicare payments to pressure relatives of the deceased to sign voluntary harvesting consent forms. This increased cardiac dead [as opposed to brain dead] harvesting in the United States 172 per cent over five years to 20,000 bodies annually. "

On January 5 2004 in the New Zealand Herald Hawke's Bay - based Barbara Sumner Burstyn wrote a column about her experience in Salt Lake City of being offered dermal fillers made of cadaver dermis to correct her frown lines. Did the donor's gift of lifesaving organs include consent to use their skin in expensive profit-heavy cosmetic procedures, she wanted to know. Sumner Burstyn's subsequent research forced her to reverse her decision to donate her organs. "We are naive if we think the free market has not extended to the organ donor business."

Four days later national transplant donor co-ordinator Janice Langiands responded with a piece reassuring that such practices do not occur here. "Donated skin is used only for burns and trauma victims and is not available privately for elective cosmetic surgery."

But it seems New Zealand cosmetic surgery patients can avail themselves of such products. North & South contacted Christchurch dermatologist and Dermatological Society president Ken Rutherford and asked whether New Zealand patients are aware some dermal fillers are made from donated human skin. He replied: "Dermal fillers are not made from donated human skin." But the society's website lists at least 17 implant substances used here and the third on the list is Alloderm. Go to www.lifecell.com and you will find it's made from "donated human tissue" recovered by US tissue banks.

To ensure Stephen Streat's brick wall is intact Janice Langlands won't use the word transplant despite the fact she manages the National Transplant Donor Co-ordination Office. And Andy Tookey's right, her number is not in the phone book and the agency's information leaflets are not freely available from driver licensing outlets. Though you could take the initiative, as Nelson donor mum Jenny Richards did, and ask Langlands to send you a box for distribution around your community.

Langlands and Kelly share donor co-ordination for the whole country, taking calls from all New Zealand's intensive care units about potential donors, organising organ retrieval, gathering the information about the donor and giving it to the transplant units so they can decide if the organs are suitable and if they have recipients they can be matched to. They then charter planes to fly teams of surgeons and nurses round the country, assist with retrievals and organise organ transport. It's a huge job. One or other, if you know their phone number, is available 24 hours a day.

"We deal with the harder side of the whole process, with the families before their loved ones go into the operating theatre and then afterwards," says Langlands.

As a Wellington-based donor mum wrote, in a poignant anonymous testimony to North & South, the agony of letting her beloved daughter's warm, still-breathing body go into the theatre for organ retrieval, donation was not an easy thing to do:

"The organ retrieval team had to be notified and brought together. They'd be ready at 4pm the nurses said. Our daughter was still ours until then, peaceful and serene in her bed with only a few scratches on her face. She could have been merely asleep. The doctors had to determine with a second obligatory test that she was brain dead, but this time I turned away. I didn't want to see them squeeze her finger nails, shine lights in her eyes. It might not hurt her any more but I felt real and debilitating pain.

"We gathered round our daughter's bed crying silently. We could see doctors beginning to arrive, hovering outside the door in their white coats, waiting for latecomers. Finally they came in together. One of the men smiled nervously to himself as they crowded into the room, no-one dared to meet our eyes. It was surreal. It was like playing a part in some ghastly horror film. Even the nurses we had grown to trust and depend on stood back in awe. It was terrible."

This woman's account makes abundantly clear the greatest gift is made by the family, not the donor.

Langiands describes the process as a "huge operation done in a normal sterile operating theatre... with a minimum of 12 people in the theatre and a lot of equipment. There's the noisy ventilator, and suction and people asking for things - not excessive noise but phones going - we're ringing transplant units to say what the organs are like. "

Langlands says the patient's body is treated with dignity and respect. After the organs are removed, surgeons suture the wounds and cover them with dressings. Nurses wash the patients and help take out lines and breathing tubes. If the retrieval is being done in the Auckland region Langlands, who is a trained nurse, does this work. "Often we wash their hair and redo dressings if they have had injuries. We care for them and respect them as we would if they were one of our own family members."

While she doesn't have any problems dealing with the operation Langlands says the time after retrieval is "always difficult. They are not breathing any more and you think about what happened to them and the tragedy of their death and whether they have young children. You always know the family will never be the same again. "

If you agree to donation you can specify which organs can and cannot be taken. "Sometimes people agree to everything and don't necessarily want it spelt out." Skin is not taken from brain dead donors in intensive care units. Nor is fascia - the thick white layers of connective tissue comprising protein and collagen which is removed and sold in the US for cosmetic implants and augmentations.

Families often say yes to everything except eye donation. If eyes are removed for corneal transplantation shields are placed under the donor's eyelids. Corneas are stored at the National Eye Bank in Auckland.

Langlands says the most difficult part is that families cannot be there when the last breath is taken and the heart is stopped. "The time the person dies is when they do the second brain death test but they come through to the operating theatre with the ventilator going, still passing urine, their blood pressure being monitored, being given drugs and cared for to maintain the organs. With brain death they don't look dead. It's really important for the family to know they have died when they do the second test."

Nelson mum Jenny Richards didn't have to be asked to donate 27-year-old son Vaughan Baillie's organs. She thought about it, asked his brothers first and offered during a meeting with Nelson Hospital ICU doctors after Vaughan's second brain death test.

The family still has no idea why their loving, big-hearted son and brother committed suicide on Monday January 25 2001. "We're still having difficulty coming to terms with it because it just wasn't him. It must have been a spur of the moment thing because after he'd done it lie fought to live," says Richards.

Baillie, a construction diver and boat salvager, was back home in Nelson following a stressful time salvaging boats in Lyttlelton Harbour when he shot himself. He was still alive when his brother Nigel found him.

Mum Jenny was away in Franz Josef -where she was running a restaurant at the time. "We got [to Nelson] in four hours but they were pretty sure there was no chance of Vaughan living. He had two wounds to his head."

Richards says ICU staff did not approach her to discuss donation, though she thinks given time they might have. "I think surgeons think it's a bad time for the family and they treat it as a negative thing. That's what I'm trying to get through to people. It's a positive thing. Nigel, Vaughan's older brother, said, when I asked him how he felt about it, 'Mum it helped me through, to know [Vaughan's death] wasn't a complete and utter waste.'

"We knew when the transplant team arrived. They set up their own theatre. We had one hour left with Vaughan. This was Thursday, about 4pm. We'd been at the hospital all the time. We were all round the bed and someone said, 'we are one very unhappy family but at least there are going to be some happy families because of it.'"

Richards says two 40-year-old men got her son's kidneys and were back at work after a couple of months "extremely glad to be free of dialysis treatment". The recipient of his liver was a woman in her early 60s "enjoying her new life with her family". Because there was no suitable blood group match for the heart and lungs the lungs were not transplanted but the aortic heart valve was transplanted into a 26-year-old man and the pulmonary heart valve into a man in his late teens. "Five families have been helped."

On discovering there were no information leaflets available Richards rang Janice Langlands who sent her two boxes. "I distributed them round Nelson, my friend did Golden Bay and Richmond. I did Motueka. My niece has taken them to Blenheim, my sister has done Greymouth and Hokitika and my local So!optimist club is looking at distributing them nationally."

Both Andy Tookey and Stephen Streat would approve.

Reproduced courtesy of North & South magazine

In the following months copies of 'North & South' (April & May Issues) there were some 'letters to the editor' in response to this article. (click here to go to them)

Note from Andy Tookey:

Since this article was published the 'medical profession’ used the same argument in a letter to the NZ Herald. (Click here to view it)

A few days after that the NZ Herald responded to the argument (click here to view it) click here to go to the 'latest news' page click here to go to the homepage

back to top

|